David Cole, national legal director of the ACLU, wrote a powerful argument about the way to stop Trump.

Whether Trump will actually try to implement these promises, and more importantly, whether he will succeed if he does try, lies as much in our hands as in his. If Americans let him, Trump may well do all that he promised—and more…

We let a minority of voters give Trump the presidency by not turning out to vote for Clinton…But if we now and for the next four years insist that he honor our most fundamental constitutional values, including equality, human dignity, fair process, privacy, and the rule of law, and if we organize and advocate in defense of those principles, he can and will be contained. It won’t happen overnight. There will be many protracted struggles. The important thing to bear in mind is that if we fight, we can prevail.

What he is suggesting is that it isn’t simply up to our representatives in D.C. to stop Trump. It’s also up to us…the American people. But a lot of folks are asking, “what does it mean to organize and advocate?” We can surely contact our elected representatives to advocate for their vote. But is there more to it than that?

The answer we often turn to are protest marches. While those can be effective in getting a message out and bolstering our feelings of not being alone in the struggle, Moises Naim reminds us that they are often limited in effecting change.

In today’s world, an appeal to protest via Twitter, Facebook, or text message is sure to attract a crowd, especially if it is to demonstrate against something—anything, really—that outrages us. The problem is what happens after the march. Sometimes it ends in violent confrontation with the police, and more often than not it simply fizzles out. Behind massive street demonstrations there is rarely a well-oiled and more-permanent organization capable of following up on protesters’ demands and undertaking the complex, face-to-face, and dull political work that produces real change in government. This is the important point made by Zeynep Tufekci, a fellow at the Center for Information Technology Policy at Princeton University, who writes that “Before the Internet, the tedious work of organizing that was required to circumvent censorship or to organize a protest also helped build infrastructure for decision making and strategies for sustaining momentum. Now movements can rush past that step, often to their own detriment.”

Sometimes, resistance involves being more creative than simply organizing a protest. As an alternative, my friend Denise Oliver Velez recently wrote about her own experience with what she calls, “Community PE,” or political education. But it wasn’t so much about educating the community as it was about educating the organizers.

In the late 60’s, a group of us from local New York colleges, inspired by the Panthers and the Chicago Young Lords, went into East Harlem—New York’s predominantly Puerto Rican community— to talk to people in the neighborhood to find out what their top concerns and issues were, so that we could move to take action on a people’s agenda.

We didn’t want to be a “top down left” pre-determining what “we” the educated leftists thought was best for folks. We wound up being surprised. It wasn’t police brutality. It wasn’t even jobs or education, though all these things were brought up. What topped the list was “garbage” or in Spanish, “la baser.”…The streets and back alleys were flooded with piles of rotting garbage, breeding rats and roaches, and those same alleys also hosted mosquitoes.

So they organized garbage pick-ups and decided to burn it (a “garbage offensive”) on a main thoroughfare. As a result:

This action gained us respect in the community. As a result, people young and old started coming to our community political education meetings. In those meetings, neighborhood folks would raise other concerns, and we would work out how we could take action, and also how we could pressure the city government to make changes.

Recently I’ve been encouraged by the actions/words of Americans that demonstrate the building of a resistance. On a small scale, how about these high school students who decided to wear hajib’s in order to show solidarity with their Muslim classmates? Taking that solidarity to the level of resistance, Jonathan Greenblatt, head of the Anti-Defamation League, said this recently:

“If one day Muslim Americans will be forced to register their identities, then that is the day that this proud Jew will register as a Muslim,” Greenblatt said.

Just imagine what would happen to such a registry if millions of Americans decided to join Greenblatt.

Beyond that, I was also encouraged by this news:

In the past week, Obama alumni have planned gatherings at Glascott’s Saloon in Chicago (an old campaign haunt) and The Winslow in New York. In Washington, they’re meeting in hotel lobbies, 14th Street bars, nonprofits’ conference rooms and living rooms, plotting the resistance over beer and hummus.

One attendee called the meetings “Obama Anonymous,” and while they largely started as impromptu commiseration, they’ve shifted to mobilization.

They are in the early stages at this point and their plans certainly include recruiting candidates to run for office. But I’m also impressed with how these (mostly young) people are thinking outside the box.

Other ideas are emerging, many still in the brainstorming stage. At one gathering on Tuesday night in a Washington living room, about a dozen current and former Obama appointees discussed creating an “action tank” – like a think tank, but more ground game than Ivy Tower – with the working title “Center for a New American Response.” According to notes from one attendee, they also kicked around the idea of an equivalent of the PeaceCorps or Teach for America to plant service-oriented progressives in the rural areas Trump won, and a toolkit to help a new generation run for local office without waiting for an open seat or working through crusty party committees.

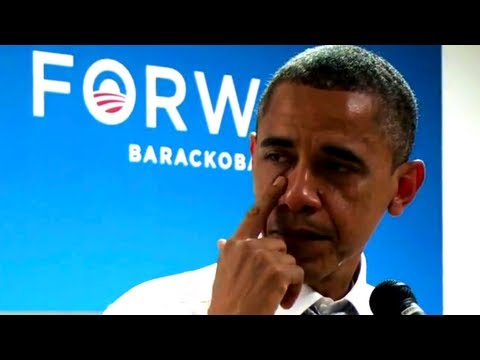

It all reminded me of what Obama said to these same young people following his re-election in 2012.

It’s also clear that soon their former boss will be doing what he can to add to their ranks. Here is what Obama told David Remnick:

“I’ll be fifty-five when I leave”—he knocked on a wooden end table—“assuming that I get a couple more decades of good health, at least, then I think both Michelle and I are interested in creating platforms that train, empower, network, boost the next generation of leadership. And I think that, whatever shape my Presidential center takes…we’ll be most interested in is programming that helps the next Michelle Obama or the next Barack Obama, who right now is sitting out there and has no idea how to make their ideals live, isn’t quite sure what to do—to give them resources and ways to think about social change.”

While we keep an eye on the president-elect and Congress, I’ll also be paying attention to how and where the resistance gets organized.